In 1964, Kitty Genovese was returning home from her job as a bartender around 3 a.m. when she was attacked – two times – and then raped and killed by the same man.

Twenty-eight years old at the time, Kitty lived with her girlfriend in Queens, New York. She had grown up in an Italian-American family in Brooklyn and was married briefly in her teens. Other than having been arrested once, Kitty lived a quiet, normal life.

On March 13, after finishing her shift at Ev’s Eleventh Hour Sports Bar, Kitty drove home and parked her car on the street. Unfortunately, Winston Moseley was also there – and he was looking for a victim.

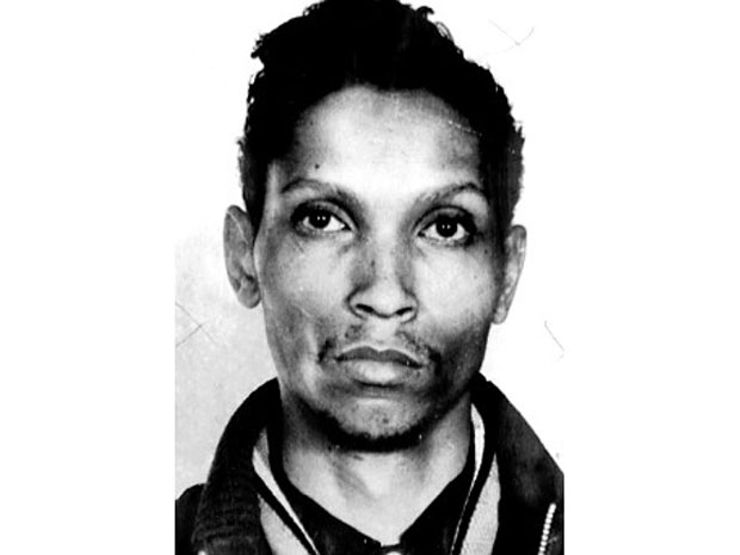

From the outside, Moseley led a very normal life – just like Kitty. He was married and owned a home, where he lived with his wife and their two children.

But he also had psychotic urges.

That night Moseley got out of bed around 2 a.m., while his wife was still sleeping. He got in his car and drove around until he saw Kitty getting out of her car.

While she was walking up the street, Moseley ran over and stabbed her twice in the back. Kitty started screaming.

One neighbor heard and yelled out his window, scaring off Moseley. Others admitted they heard the commotion, but they thought it was a brawl from the bar nearby, so they went back to bed. No one came outside to help.

Fatally wounded, Kitty staggered around her building to the back entrance. Moseley hid a couple of blocks away in his car.

When the police failed to arrive about 10 minutes later, Moseley ventured out, searching for Kitty.

He found her in the lobby of her apartment building. He stabbed her again, raped her, stole $49 she had on her, and ran.

Inside the building, Kitty’s neighbor, Karl Ross, opened the door and observed the attack, but instead of coming to help, he, now famously, slammed it shut again. Some reports claimed Ross then called the police, although when interviewed, he said he didn’t want to get involved.

The total time it took Moseley to kill Kitty was a harrowing half hour.

A couple weeks later, the New York Times reported that 38 witnesses had heard Kitty’s screams. Although the exact number has been debated since – in Kitty Genovese: The Murder, the Bystanders, the Crime That Changed America, author Kevin Cook stated 49 neighbors were interviewed – the fact remains that no one came to help.

Moseley remained at large until he was apprehended for stealing a television set from a home in Queens. While at the police station, he confessed to Kitty Genovese’s murder, two other homicides, and dozens of burglaries. According to the Daily News, Moseley said he just wanted “to kill a woman.”

Kitty was at the wrong place at the wrong time.

After a sensationalized trial, a jury convicted Moseley of murder, attempted kidnapping, and robbery. He was sentenced to death, but an appeal reduced it to life in prison.

The American public was still shocked and outraged that a young woman had been murdered with so many witnesses at the scene.

Social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley came up with a theory called The Bystander Effect, which hypothesized that it’s more likely for someone to intervene in a situation if there are only a few witnesses. In a large group, people take cues from each other – or they think someone else will take action, so they don’t have to.

The other social movement to emerge from Kitty’s tragic death was the creation of a universal emergency phone number. At the time, the only way to reach the police was to call your local precinct. Today, the three-digit number is used across North America.

Public fascination with the case hasn’t waned in the last 51 years: Fictionalized accounts of Kitty’s story can be found as a made-for-TV movie Death Scream, a Law & Order episode, and the thriller novel, Victims, by Dorothy Uhnak.

[via Daily News; NPR; Psychology Today]

Photos: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; W. W. Norton & Company; Open Road Media