From 2007 to 2008, Gary Hilton stalked the backcountry paths of national parks throughout the southern United States, leaving a trail of death in his wake.

But the crimes of the man they called called the National Forest Serial Killer were about to come to a crashing end.

True crime writer Fred Rosen, author of Trails of Death: The True Story of National Forest Serial Killer Gary Hilton, returns with the second installment of his three-part exclusive on the hunt for Gary Hilton through the forests of North Carolina, Florida, and Georgia.

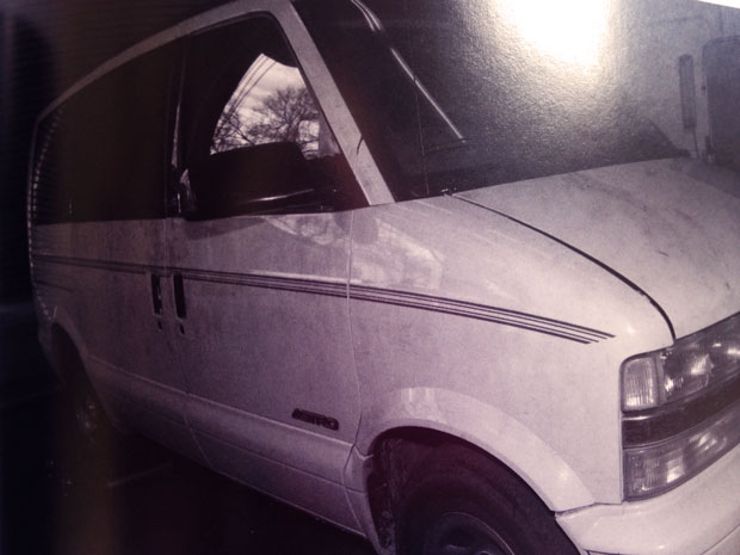

In 2005, roughly two years before he claimed his first victim, serial killer Gary Hilton abandoned a van in the Tray Mountain area of White County, Georgia. He received a citation for doing so, but didn’t answer it. A warrant for his arrest was issued and put into the Federal database.

Here’s the thing about serial killers: They don’t just start murdering in their 60s. Something has to set them off, or seriously disturb their day-to-day lives.

The worst you could say about Hilton before he committed murder was that he was a conman and petty thief. But that all changed when a Georgia physician prescribed him Ritalin, despite the fact he did not suffer from ADD.

Serial killer Gary Hilton’s Dodge Astro Van

Serial killer Gary Hilton’s Dodge Astro Van

In Georgia, Hilton had worked for years as a “tin man” for John Tabor, who ran a home siding business in the Atlanta area. Tabor not only employed Hilton, he provided him a home on one of his properties. Soon after Hilton began taking Ritalin, which acts as a stimulant for those without ADD, his demeanor changed. He grew irritable and confrontational, acted out, even threatened Tabor with violence. It wasn’t long before Hilton lost his job and his home on Tabor’s property.

Cut loose, Hilton hit the road in his Chevy Astro van with Dandy, his dog and ever-present companion, popping Ritalin as he went. Hilton preferred national parks, and so he headed north, leaving Georgia in 2007 and entering North Carolina’s Pisgah National Park. How he came to befriend Irene and John Bryant, senior citizens married for 55 years, is unknown.

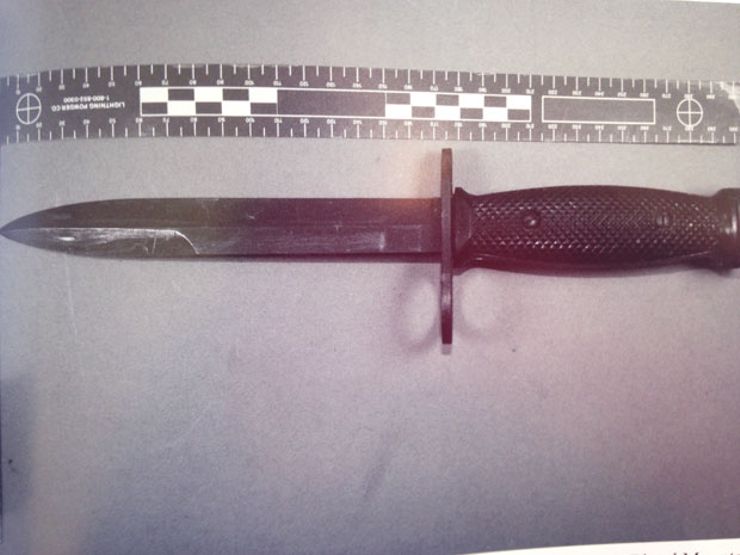

A murder weapon used by Gary Hilton

A murder weapon used by Gary Hilton

What is known is that shortly after the couple went hiking on October 20, 2007, they disappeared. Someone used the couple’s ATM card at a bank 75 miles away. Irene turned up dead roughly three weeks later on November 9, her skull fractured in multiple places. John remained missing. His body wouldn’t be found until 2008.

Hilton, meanwhile, left North Carolina, driving south into Georgia. He stopped to set up camp on a private hunting preserve in Cherokee County. A local noticed his presence and called police to make a complaint; a deputy drove out to kick Hilton off the property. Upon arrival, the deputy ran Hilton’s license through a state database; no outstanding warrants in the Peach State. At the time, there was no requirement that the license be run through the Federal database, so it wasn’t.

If Hilton’s license had been checked at the federal level, the deputy would have caught his outstanding warrant for that unanswered citation from 2005. Hilton would have been arrested there and then, two people would be alive, and this article would stop right here.

Sadly, nothing of the sort took place. The deputy told Hilton to pack up his gear and clear out. He was free to go.

Cheryl Dunlap, one of Hilton’s victims

Cheryl Dunlap, one of Hilton’s victims

Leaving Cherokee County, Hilton drove south, crossing into Florida and entering the Apalachicola National Forest outside Tallahassee by the middle of November. Despite another run-in with a park service officer on November 17, Hilton was let go with a warning not to exceed the park’s 14-day camping limit. And once again, his name was not cross-referenced in a federal database for outstanding warrants.

The details surrounding Hilton’s abduction of 46-year-old nurse Cheryl Dunlap on December 1, 2007 in the Apalachicola National Forest remain a mystery. Just five feet four inches, Dunlap had thick wavy brown hair, brown eyes, and thin lips. She was a mother and devoted member of the evangelical Christian River of Life Church. Soon after her disappearance, Cheryl’s car was found with a flat tire on Crawfordville Highway parked just outside the park’s entrance. She may have been attempting to flag someone down for assistance when Hilton came upon her.

The mask used by Hilton while withdrawing money from the bank accounts of his victims

The mask used by Hilton while withdrawing money from the bank accounts of his victims

A few days after the discovery of Cheryl’s car, security camera footage surfaced of a man in a rubber mask attempting to use Dunlap’s bankcard at area ATMs. Then on December 15, Apalachicola park rangers noticed buzzards picking over a large carcass. They realized it was the body of a woman as they grew closer, with gaping wounds on the torso and legs. Then they noticed what wasn’t there: Both hands had been cut off, and the head was missing.

The body would eventually be identified as the missing Cheryl Dunlap.

While authorities scoured the area for clues to their killer, Hilton hit the road. By the end of 2007, he was back in Georgia, just in time for New Year’s Eve.

On January 1, 2008, Hilton and Dandy set out for a hike on Blood Mountain outside of Atlanta. That’s when he ran into Meredith Emerson, who was also enjoying a New Year’s Day trek with her dog.

Hilton tried abducting her, but the martial arts-trained Emerson resisted. A powerful 24-year-old, Emerson put up a good fight. But Hilton, trained in hand-to-hand combat from his days in the Army, eventually got the better of her. Once subdued, he marched her down the mountain to his van.

Meredith Emerson’s wallet

Meredith Emerson’s wallet

Inside, he tied Emerson down, drove away and held her prisoner for days. This time, however, Hilton failed to clean up his trail. Other witnesses had seen them on the mountain that day. They alerted authorities and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation soon identified Hilton as the primary suspect in Emerson’s abduction. Police continued to scour Blood Mountain, despite the fact that attempts to use Emerson’s bankcard had been made at ATMs many miles away.

News of the abduction went national. It soon caught the attention of John Tabor, Hilton’s former boss at the siding business. When Hilton called him to ask for money, Tabor knew Hilton was the prime suspect in Emerson’s disappearance. Strangely, Tabor waited over an hour to inform the Georgia Bureau of Investigation about the call.

Authorities were able to trace it to a pancake house off of Blood Mountain. By the time they arrived, however, Hilton was gone.

Gary Hilton’s cluttered van

Gary Hilton’s cluttered van

A few days later, in DeKalb County, Hilton was spotted in a parking lot, removing items out of his van and tossing them into a dumpster. A phone call was made.

“The guy you’re looking for is cleaning out his van,” the witness told police in a 911 call.

DeKalb County deputies rushed to the scene, their sirens screaming and dome lights flashing. This time, Hilton didn’t have time to escape. He offered no resistance as police put him into custody. Soon, Hilton found himself in an interview room, turned over to the GBI. He readily admitted to killing Emerson, speaking in bursts. He was looking to make a deal.

In exchange for a full confession and leading Georgia police to Emerson’s body, Hilton would get life in prison without possibility of parole. He did just that. Under heavy escort, Hilton led authorities to a remote road in Dawson Forest, 35.7 miles south of Blood Mountain, where he had buried Emerson’s body. Clearly, the GBI had been looking for Emerson in the wrong place. Just like Dunlap’s corpse, the head was gone. I buried it nearby, Hilton told police. He had beheaded Emerson in an attempt to obscure identification.

As Georgia authorities pieced together the murder of Meredith Emerson, Florida law enforcement officers were connecting the dots between Emerson and Dunlap; their killer was the same guy. But unlike Georgia, Florida was not going to make a deal.

***

Join us next week for the concluding installment of Trail of Death: The Hunt for Gary Hilton

True crime writer Fred Rosen is the author of numerous books, including Lobster Boy, Deacon of Death, Did They Really Do It? and Needle Work. His book on the Hilton case is Trails of Death: The True Story of National Forest Serial Killer Gary Hilton.

Cover of "Trails of Death: The True Story of National Forest Serial Killer Gary Hilton" via TitleTown Publishing; All other photos courtesy of the author