From the outside, Joan Robinson Hill’s life looked like a fairy tale. Born Joan Olive, she had been given up for adoption at a young age by her unmarried mother and had been taken in by a Houston oil baron named Davis Ashton Robinson—known as “Ash” to his friends—and his wife Rhea, when they discovered that Rhea could not have children of her own.

As a child, Joan was “as well attended as a czarina,” according to journalist Thomas Thompson, who would later write about her tragic and mysterious death. Joan’s adopted parents seemingly doted on her, and she became an equestrian at a young age, going on to compete all over the country, winning hundreds of trophies, often with her aptly named favorite horse, Beloved Belinda.

However, Joan’s life was also marred by difficulties. She was married and divorced twice before she reached the age of 20, with both marriages lasting less than a year. Then, in 1957, she married John Hill, described by the Houston Chronicle as “one of the city’s leading plastic surgeons.” The two became a fixture of the Houston social scene and moved into a mansion in the wealthy River Oaks neighborhood. By that time, they had a five-year-old son named Richard, but according to later accounts the two already “largely led separate lives.”

Though he was a successful plastic surgeon, John Hill was deeply in debt to his father-in-law. John’s passion was music, and he spent at least twenty hours per week on everything from lessons to practice to attending or performing in concerts. He also dumped more than $100,000 into the construction of an ambitious music room in their home, one that is believed to be “one of the most acoustically advanced in the country,” according to reporting from The Paris News.

John’s dedication to music was a bone of contention in his marriage to Joan, but it was far from the only one. John was also having an affair, and by November of 1968, he served his wife with divorce papers. Pressure from John’s father-in-law helped the couple to reconcile, at least temporarily, though John continued seeing his mistress, a woman named Ann Kurth whom he had met when picking Richard up from summer camp.

The situation seemed untenable and it proved to be exactly that. Within three months of their reconciliation, Joan Robinson Hill was dead.

Was It Murder? The Mysterious Death of Joan Robinson Hill

Joan Robinson Hill and John Hill

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons ImagesTwo guests were staying with the Hills when Joan’s illness began. On March 15 of 1969, Joan began vomiting, and was eventually confined to her bedroom for rest. By March 18, Joan was only semiconscious, and her husband took her to the hospital, though he refused to call an ambulance and instead drove her himself, taking her to a hospital some forty minutes away without emergency or intensive care facilities.

In less than 24 hours, Joan Robinson Hill was dead. John Hill was present in the hospital, and it is said that his cries were so loud that they were heard by patients on another floor. Despite this, he would shortly find himself charged with her murder.

The beginning of the charges stemmed from the fact that John Hill ordered his wife’s body to be taken away immediately by a funeral home. Within five hours of her death, Joan’s body was already in the process of being embalmed, despite the fact that Texas state law required an autopsy for anyone who died in a hospital within 24 hours of admittance.

Several autopsies followed but were ultimately unable to determine a definite cause of death, partially due to the interference caused by the premature embalming. Ash Robinson used the considerable influence that his fortune lent him to push for the District Attorney to launch a murder investigation, ultimately leading John Hill to be the first person ever indicted by the state of Texas on the charge of “murder by omission,” as the jury found that he had intentionally contributed to his wife’s death by not getting her medical care sooner. There was yet another complication waiting in the wings, however…

Gunned Down Before He Could Stand Trial

Following Joan Robinson Hill’s death, John Hill had married his mistress, but their matrimony didn’t last long. At his murder trial, Ann Kurth testified against him, claiming that he had confessed to her that he had murdered his first wife, and that he had tried to kill her on three separate occasions. Unfortunately, because her testimony contradicted the prosecution’s case of “murder by omission,” it opened up an opportunity for John’s lawyer to move for a mistrial.

His second murder trial was scheduled to begin in November of 1972, but John didn’t live to see it. On September 24, 1972, John was gunned down by a masked killer when he interrupted an apparent robbery at the same mansion where he and Joan had lived.

Bobby Wayne Vandiver and two accomplices were arrested for the murder of John Hill. Vandiver said that it had been a contract killing, and that he had been paid $5,000 to end John Hill’s life. Who ponied up that money? Many people suspected Hill’s father-in-law, but the truth, whatever it might have been, never came to light, as Vandiver himself was gunned down shortly thereafter, this time by a police officer in Longview, Texas, where Vandiver had fled to avoid trial.

This seemingly put an end to the case, albeit without much in the way of closure. But any murder as mysterious and high profile as this one was bound to leave behind ripples and make a mark on popular culture.

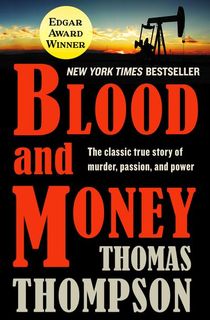

Blood and Money by Thomas Thompson

Journalist Thomas Thompson first heard about the case while he was researching his 1971 book Hearts, which chronicled the rivalry between two Houston-based cardiac surgeons. By 1976, just four years after the murder of John Hill, Thompson had published Blood and Money, a tell-all account of the case that sold over four million copies and netted the author some three lawsuits.

Both Ann Kurth and Ash Robinson sued Thompson over how they were depicted in the book, as did the Longview, Texas officer who slew Bobby Vandiver. All the suits were ultimately unsuccessful, though they did tie up Thompson’s royalties until all three were resolved. Despite—or perhaps because of—this controversy, the book was a bestseller, winning Thompson an Edgar Award.

Nor was Thompson the only one to write an account of the events surrounding the death of Joan Robinson Hill. Ann Kurth wrote her own version of the story, which suggested that John Hill had not, in fact, been gunned down at his home, but had faked his own death and fled to Mexico, elements which were eventually used in the 1981 made-for-TV movie Murder in Texas.

Murder in Texas and Where They Are Today

Released as a two-part mini-series in 1981, Murder in Texas received a Golden Globe nomination, and also nabbed Andy Griffith his only Emmy nomination for his portrayal of Ash Robinson. Besides Griffith, the film starred Sam Elliott (shockingly without a mustache) as John Hill, Farrah Fawcett as Joan Robinson Hill, and Katharine Ross as Ann Kurth. Adapted from Ann Kurth’s book Prescription Murder, it was one of the most popular programs on TV for the two weeks that it aired.

In the years since, there have been reported—albeit unconfirmed—sightings of John Hill everywhere from New York to Mexico, and the Joan Robinson Hill story has been the subject of several true crime shows, including episodes of Behind Mansion Walls and the podcast My Favorite Murder.

In 1981, the same year that Murder in Texas hit the airwaves, the family mansion was put on the market by a combined effort from Ash Robinson and his grandson Richard Hill.

“I just can’t afford to keep it up,” Richard Hill told The Paris News. “Owning a big house is a big responsibility, particularly for someone as inexperienced as I am.”

By then, Richard Hill was 21, and was attending school in Colorado Springs. The unexplained deaths of both his parents had been hard on Richard, driving a wedge between him and his maternal grandfather, who called him by the nickname “Boots.”

By the time the two put the family home on the market, however, Richard said that the rift had healed. While letting go of the one-of-a-kind mansion couldn’t have been an easy decision for the young Hill, it’s also true that the house where both of his parents had met their untimely ends couldn’t have held too many positive associations for him, either.