A celebrity’s death often comes as a public shock … especially if it’s particularly gruesome or shrouded in mystery.

In Coroner, Hollywood’s renowned medical examiner Dr. Thomas Noguchi reveals never-before-disclosed details of the high-profile, controversial death cases he has worked on … including the mysterious demise of beloved actress Natalie Wood.

Wood was found drowned near her yacht during a holiday celebration in 1981. While cause of death was apparent, the circumstances behind her death were not: Why was she out in the middle of the ocean by herself? Was she trying to escape something happening on the boat? Was there foul play involved?

Read on to find out the details behind the case in Noguchi’s in-depth recounting in Coroner.

Medical Examiner’s Case No. 81-15167: Natalie Wood

[Natalie Wood and husband Robert Wagner] were very much in love and delighted in their children, Katherine, who was 16 in 1981, Natasha, 11, and Courtney Broome, seven.

Their marriage was enhanced by another love: the sea. And recently their lives had revolved around Splendour, on which they spent most of their weekends and holidays. Natalie Wood, contrary to some reports, did not seem afraid of the water at all. Fellow sailors often saw her skimming around the harbor alone in the little rubber dinghy that served as a tender for the yacht.

In 1981, as the Thanksgiving holiday weekend approached, both Wagners were, as usual, enjoying professional success. Robert Wagner, known as R.J. to his friends, was co-starring with Stephanie Powers in a highly rated television series, Hart to Hart. And Natalie Wood was making Brainstorm, an MGM motion picture in which her co-star was Christopher Walken. The Wagners invited Walken to join them on their yacht in Catalina for the holiday weekend.

Bad weather was predicted for the night of November 28. A cold piercing rain swept over Isthmus Bay, pummeling the faces of those going ashore in small boats for dinner. But the sea was not rough, and the dinghies had no difficulty negotiating the waves. Twice, earlier that day, [our chief consultant on ocean accidents] Paul Miller had seen Natalie Wood “buzz” in to shore in her dinghy alone. Then, at about 5 P.M., Miller and three friends eased their own dinghy into a dock and a few minutes later entered the warmth and brightness of Doug’s Harbor Reef, where they noticed a party already under way at one table. Natalie Wood, Robert Wagner and Christopher Walken were gaily drinking champagne.

About 7 P.M. the Wagner party was seated for dinner, with which they ordered more champagne. They were still enjoying themselves when Miller and his friends left. But Don Whiting, the night manager of the restaurant, was worried. He felt that the Wagners were so intoxicated they might not make it back to their yacht. When they left the restaurant at 10:30 P.M., he called Kurt Craig of the Harbor Patrol and asked him to make certain the group reached their yacht safely in the dinghy.

Later that night, aboard Easy Rider, Miller and his wife couldn’t sleep. Their quarters were in the bow of their boat, facing the shore, and in a house on that shore a party was raging. Two loudspeakers had been set up on a porch, and the sound of rock music blaring across the cove was keeping the Millers awake. This may have been the party noise which Marilyn Wayne, who heard Natalie Wood’s cries, believed was coming from another boat. At 1:15 A.M. Miller sat up, reached wearily for the radio microphone, and turned to the harbor channel, which all boats monitor. He intended to call the Bay Watch, the private Isthmus Bay Coast Guard detail, to ask them to quiet the party on the beach.

Natalie Wood and Robert Wagner

“Bay Watch, this is Easy Rider.”

Nothing but crackling static, and Miller realized at once that the man from the Bay Watch must be at the party.

Suddenly the radio sprang to life with a different voice. It was Robert Wagner, although Miller didn’t recognize his voice at first. He didn’t sound nervous or excited. Miller described Wagner’s tone as “quizzical” as he said, “Easy Rider, are you cruising in the vicinity?”

“No.”

“Well, this is Splendour. We think we may have someone missing in an 11-foot rubber dinghy.”

Don Whiting, the night manager of the restaurant, was reading a paperback book in the cabin of the boat on which he lived year round, when the radio beside him crackled and he heard the conversation between Wagner and Miller. Whiting radioed a friend on the isthmus to go to the Wagner yacht at once and report back to him about the situation.

Thirty minutes later, light beams from Harbor Patrol boats, private boats of the Bay Watch, and Coast Guard helicopters began to crisscross the ocean. The beams illuminated rolling waves and “swept over yachts and sailing ships rocking in the swells—but nothing was found in the sea.

At 7:30 the following morning a Sheriff’s Office helicopter was heading toward Catalina to aid in the search when suddenly one of the crew members detected a spot of red in the ocean waves below. “Go down,” he shouted to the pilot. The helicopter descended toward the sea, the wind from its rotor blades churning the water beneath them. Face down, in a red jacket, Natalie Wood floated, her hair splayed out in the water.

The location of her body was no less than one mile south of the Wagner yacht, off an isolated cove known as Blue Cavern Point. The missing dinghy was discovered on the shore, even farther to the south. The key in the ignition of the boat was turned to the off position, the gear was in neutral, and the oars were tied down.

Police were surprised, because the boat obviously had not been used. Even more startling was Natalie Wood’s clothing. She was clad only in a nightgown, knee-length wool socks and a down-filled jacket. It was apparent that she had not dressed for a boat ride—and yet police believed she must have untied the line which held the dinghy to the yacht. But why had she untied it if she didn’t intend to go out in the boat? That was only one of the mysteries surrounding her tragic death.

***

On the day Natalie Wood’s body was found, I dispatched Pamela Eaker, a skilled investigator on the Medical Examiner’s staff, to Catalina. Eaker interrogated Robert Wagner, who told her that after they had returned from the restaurant that night he and Walken went to the wardroom of the yacht for a nightcap while Natalie retired to her quarters. The last time he remembered seeing his wife was at about quarter of eleven. Then, sometime after midnight, Wagner went to their cabin and noticed that his wife was not in bed. When he searched for her elsewhere on the yacht, he discovered that the dinghy was also missing. Even so, he said, he wasn’t concerned at first, because his wife often took the boat out alone. But as time passed and she didn’t reappear, he became more and more upset, and finally radioed for help.

Eaker asked Wagner if it was possible that his wife had taken her own life. Wagner said that his wife was definitely not suicidal.

Eaker also spoke to Don Whiting, the restaurant manager, and to various sheriff’s deputies and Santa Monica detectives. Her official report described the findings up to that point in the investigation and concluded:

Decedent’s body had been taken from the ocean and placed in the Hyperbaric Chamber for safe-keeping. Upon this investigator’s arrival at location, decedent observed lying in “stokes litter.” Decedent is wrapped in plastic sheet, she herself is dressed in flannel nightgown and socks. The jacket that she was wearing when found floating is no longer on the body, having come off when she was pulled from the water. At time decedent was pulled from the water, Sheriff’s personnel say that body was absent of any rigor and they noted foam coming from mouth. Decedent still has foam coming from mouth. Rigor is now present of a 3 to 4+ throughout her entire body. Decedent has numerous bruises to legs and arms. Decedent’s eyes are also a bit cloudy appearing. No other trauma noted and foul play is not suspected at this time.

Nor did police suspect foul play in Natalie Wood’s death, but by nightfall on that Sunday Hollywood was alive with rumors. Wasn’t it strange that the two men on the yacht didn’t even know that she had left the boat? Hadn’t she spoken to them? Why had she slipped out to the stern of the yacht in the middle of the night, climbed down a ladder, and untied the dinghy? What was she doing? Where was she going? And why?

In any case of unusual death, it is the first duty of medical examiners to suspect murder. Indeed, some authorities on forensic science argue that the search for murder is our only real mission, and that anything else we accomplish is merely additional service to the community above and beyond that primary duty.

I believe that forensic science is—and should be—broader in its horizons. But I concur with those authorities in one particular: every death is a homicide, until proven otherwise. So, even while Pamela Eaker was interrogating people on the island, I was telephoning Paul Miller, my host on that fact-finding mission three years before. I wanted a special investigation to be conducted by an expert to determine the facts of Natalie Wood’s death. And when I learned that Miller had been there at Isthmus Bay that very night, I was convinced his report would be conclusive.

I gave Miller some specific instructions which were basic to any forensic investigation of such a tragedy:

1. Examine the stern of the Wagners’ yacht for any disturbance, or evidence of violence, that the police might have missed.

2. Check the dinghy for any sign of a struggle.

3. Examine the algae (marine plant growth) on the bottom of the swimming step for signs of disturbance. (Did she try to reboard the yacht?)

4. Check the sides of the dinghy for fingernail scratches. (Did she try to climb into the dinghy?)

Splendour

But these questions should be only the beginning, I stressed to Miller. I was relying on his experience and knowledge for the complete investigation.

When I hung up, I was pleased that I had commissioned the right man in the right location for the job. But I also knew that his special report might take days, and the public was demanding to know now what had happened to Natalie Wood. That first morning the whispers were of murder, and I could not deny them. But I hoped that with the information contained in Eaker’s fine investigative report, plus the findings of the autopsy to be performed the following day, I would obtain enough data to form a preliminary opinion on the cause of her death, and to replace rumor and speculation with official facts.

That Monday morning, November 30, 1981, was hectic for me. Dr. Sugiyama and Dr. Ishikawa (who was a classmate of mine at Nippon Medical School) were conducting a seminar in forensic science, and I was scheduled to give a breakfast talk to the seminar. But meanwhile the Medical Examiner’s Office was besieged by the press, demanding answers to the mystery of Natalie Wood’s death. I attended the meeting, said a few words, then apologized for having to leave early.

By 9:00 A.M. the autopsy was ready to begin. It was performed by Dr. Joseph Choi, one of my most skilled deputy medical examiners and Board-certified forensic pathologists. But in supervising the autopsy, I noted some intriguing facts:

A recent diffuse (widespread) bruise, measuring approximately four inches by one inch, spread over the lateral aspect of Natalie Wood’s right arm above the wrist. On the left wrist was a slight superficial fresh bruise about a half inch in diameter.

Numerous small superficial skin bruises measuring approximately a half to one inch in diameter were scattered over the right and left lower legs. They appeared to be relatively fresh. The left knee area showed a recent bruise measuring approximately two inches in diameter.

The right ankle had a recent bruise measuring about two inches in diameter, and there were small superficial bruises on the posterior aspect of both lower legs, each measuring a half inch to two inches.

A vertical brush-type abrasion on the left cheek was the only head wound, and there were no deep traumatic injuries to the skull.

An examination of the clothing Natalie Wood had worn that night revealed other significant facts. More than 24 hours after she had been found, the flannel nightgown, the wool socks and the red down jacket were still wet. I picked up the jacket and noted that it was extremely heavy, probably between 30 and 40 pounds in its saturated state. I also noted that a report from the toxicology laboratory revealed that the alcohol content of Natalie Wood’s blood was .14 percent, .04 percent above the intoxication standard as set by the California Vehicular Code.

From the toxicology report and the bruises we were able to determine the probable cause of death. The vertical abrasion on her cheek told us that Natalie Wood, possibly attempting to board the dinghy, had fallen into the ocean, striking her face. Because she had sustained no deep traumatic head wounds, we knew she had been conscious while in the water. The bruises on her lower legs, I believed at the time, were incurred during her fall.

The saddest part of the story, as far as I was concerned, was revealed in the clothing she had worn. The reason she drowned was the great weight of the jacket, which had pulled her down when she attempted to climb into the dinghy. If she had just taken off that jacket, she might easily have made it into the dinghy, and survived.

The reason she hadn’t removed the killing jacket was suggested in the report from the toxicology lab. That .14 percent of alcohol in her blood was, I believed, a deadly factor. She couldn’t have been thinking clearly, or she would have slipped off the jacket at once.

On the basis of the autopsy and the other tests we had completed up to that point, I concluded that Natalie Wood had drowned as a result of that wet jacket. I surmised that the untied dinghy, and her body, had drifted a mile away from the yacht on the current. But a question haunted me. When she first fell off the swimming step into the water, why didn’t she simply swim a few strokes and reboard the yacht by way of the step? It must have been only a few feet away from her. Even with the heavy jacket, she could have accomplished this effort easily, it seemed to me, for the step, unlike the dinghy, was stable.

Perhaps my investigator on the scene, Eaker, would provide an answer to that mystery. I sent word for her to join me in my office at noon, along with Dr. Ronald Kornblum, the deputy chief of the forensic medicine division, and Dr. Choi, who had performed the autopsy.

My office was on the second floor of Los Angeles County’s Forensic Science Center, and we met there as scheduled. The two senior pathologists, Richard Wilson, my administrative chief of staff, and investigator Eaker sat across from me as I outlined my preliminary finding of an accidental drowning, adding that alcohol had played a significant role in Natalie Wood’s death. One of my staff said, “What the reporters out there are really interested in, Dr. Noguchi, isn’t so much whether Natalie Wood was intoxicated or not, but why she left the yacht in the middle of the night.”

I nodded. The question tied in with my own. Why hadn’t she climbed back aboard the yacht when she was only one or two feet away? Both actions seemed to indicate that she was determined to get away from the yacht. It was then I was told that one of the sheriff’s deputies had apparently reported that Wagner and Walken were quarreling in the main cabin that night. In theory, it was possible that Natalie Wood became disgusted with them and tried to take off in the dinghy just to get away.

Silence filled the room. All of us were taken aback by the implications of this idea. It fed right into the hands of those who had been speculating that some “scandal” on the yacht had contributed to the famous star’s death.

***

When Paul Miller’s report on the real facts of the death of Natalie Wood arrived, I read it—and decided not to release the document to the press. It added details the media would only call “gory” and “sensational.” The report did not alter the official coroner’s conclusion of an accidental drowning. So, rather than create more media indignation over “too many details,” I reluctantly filed away that report. This is the first time the facts it uncovered, which re-create Natalie Wood’s last moments, have been revealed by me. And it is both a tragic and a heroic story.

Rereading the report today, I can see Isthmus Bay again in my mind’s eye, dark and threatening in the night, the cold rain slanting down upon ships rocking in the water. And I recall the day Miller brought me the report. We sat in my apartment in Marina Del Rey, overlooking the same ocean which broke against the shores of Santa Catalina thirty miles to the west.

Walken, Natalie Wood, and director Douglas Trumbull on the set of Brainstorm

Miller leaned toward me earnestly as he said, “You had it wrong, Tom. Natalie Wood didn’t die like you think. She had class.”

He drew a map of Isthmus Bay showing where the boats, including Splendour, were moored that night. Then he drew an arrow from the west, passing through the island mountains and pointing toward the ships in the bay. “The basic factor is the wind funnel,” he said.

From my own observations of the island on my trip three years before, I knew the phenomenon to which he referred. The jet stream sweeps from the west over Catalina Island, and in the mountains it forms a funnel which blows straight down into the bay where the Wagners’ yacht was moored. Splendour faced into the wind, as did its dinghy tied to the stern.

“After she untied the line,” Miller continued, “the dinghy would have been blown out toward the mainland. It would never have made a ninety-degree turn and headed down the coast with the wind funnel hitting it from the side. Remember, an inflatable boat in the water is like a balloon with the wind blowing it.”

It was cold that night when Natalie Wood, dressed only in a nightgown, wool socks and a down jacket, appeared on the deck of Splendour and descended the swimming step to the dinghy. Was she angry at her husband and rushing off alone? Forensic evidence, such as the fingernail scratches on the side of the dinghy, the brush-type abrasion on her cheek, and the untouched algae on the swim step, seemed to indicate that she was trying to board the dinghy, not just adjust its rope, when the accident happened.

But Miller’s evidence provided the possibility of a third explanation, which, according to my interpretation, confirmed Wagner’s story of the accident. Considering the wind funnel, when Natalie Wood, for whatever reason, untied the boat, the wind was strong and would have pushed it away from the yacht. And it is quite possible that, instead of trying to step into the dinghy, she might have been reaching for it and lost her balance.

Whatever her purpose, she fell—and the cold water closed over her head. But when she bobbed to the surface, she must have felt there was no danger. She was still only a few feet away from the safety of the yacht. Not only that, she had taken hold of the inflatable boat. The widespread bruise on her right arm showed that she hooked her arm over the side of the dinghy, knowing the boat would hold her up safely until she caught her breath.

Too late, she must have realized something strange was happening. She and the dinghy were being swept swiftly away from the yacht—10 yards, 20, 30. She hadn’t realized the strength of the wind funnel. Within seconds the dinghy was moving farther and farther out in the water, too distant for her to swim back to the yacht.

She must have called out for help at that point. But her cries went unheard on Splendour, and on other vessels too. The rock music blaring from loudspeakers at the party ashore drowned out Natalie Wood’s desperate calls from the surface of the dark sea. Yet there was still hope. Miss Wayne and her friend did hear her shouts. But when they looked outside, they could see nothing in the dark, and they thought they heard people on a neighboring boat say they were coming to her rescue.

Now Natalie Wood was no doubt becoming really frightened. Her cries were going unheard. No lights played across the water, no boats started out to her rescue. Still, she felt she was safe because of the dinghy. She could crawl into it, start its engine, and be back to the warmth of the yacht in minutes.

But it was then that she must have suffered her most terrifying shock. She tried to climb aboard the dinghy which would save her, and discovered she couldn’t do it. The rubber sides of the dinghy were large and cylindrical; it would have been difficult in the best of circumstances for her to reach over them from the water to hoist herself up. Forensic evidence revealed that she may have gone to the rear of the boat and used the motor for leverage. There was a metal frame beneath the motor in which you can place your foot. Swimmers often use this technique: with your back to the dinghy, you place one arm around the motor and a foot in the brace, and push up to board the dinghy from the water. The bruises on the back of Natalie Wood’s lower legs suggested she may have tried to do that.

But it didn’t work. She couldn’t make it into the boat. Frantically, she attempted again and again to hoist her body up into the safety of the dinghy—but the jacket dragged her back down into the water every time.

Finally she realized she was being swept into mortal danger as the dinghy pulled her farther and farther out toward the open sea. She might drown or die of hypothermia, the loss of body temperature, in the icy water. What could she do?

Natalie Wood fought for her life in that cold November ocean. She did not give up. Instead, she began to perform a feat that was both unique and gallant. And she almost achieved a miracle.

Clinging to a boat being swept out into the open sea, her body already becoming numb in the cold water, she decided that her only hope was somehow to propel that dinghy into the teeth of the wind, back toward the shore of Catalina. It must have seemed hopeless at first. The wind pushed the boat like an air bubble. But, desperately, she started kicking her legs as hard as she could, and paddling the water with her free arm.

And it worked. The boat ceased its movement out to sea and started, ever so slowly, back toward the island—and safety.

A mild current of one knot was running south, and, paddling in a dark, windy sea beside the dinghy, she pushed the boat along with the current, edging it ever closer toward the shore. But the southern drift took her away from the safe harbor with its yachts whose lights shone in the distance. In fact, the bay was now behind her. But she was approaching closer and closer to the beach—400 yards, 300 fifty yards. If she could just hang on, she would be safe on the shore.

But numbness now crept all through her body. The heavy jacket pulled her down, and its weight sapped her strength. Fighting in the ocean, she saw the cove ahead. Blue Cavern Point. No boats lay at anchor there, but it was a haven from the wind which was her enemy. Minutes to go. She must keep paddling.

Natalie Wood, a brave young woman, tragically lost her fight against the specter, death, less than 200 yards from shore. Hypothermia caused her to lose strength, then consciousness, then finally her last feeble grip on the boat. She sank beneath the waves and drowned.

Only minutes later, the boat she had so painfully and courageously maneuvered for a mile landed safely on the beach.

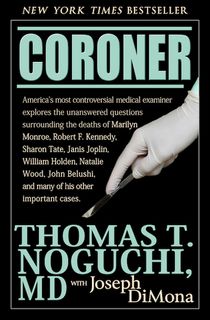

Want to know the details behind Marilyn Monroe, Janis Joplin, and John Belushi’s coroner reports? Download Coroner on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and iTunes.

Photos (in order): Hulton Archive / Getty Images; Hulton Archive / Getty Images; Keystone / Getty Images; Kent Nishimura / Getty Images; Wikimedia Commons; MGM; AFP / Getty Images